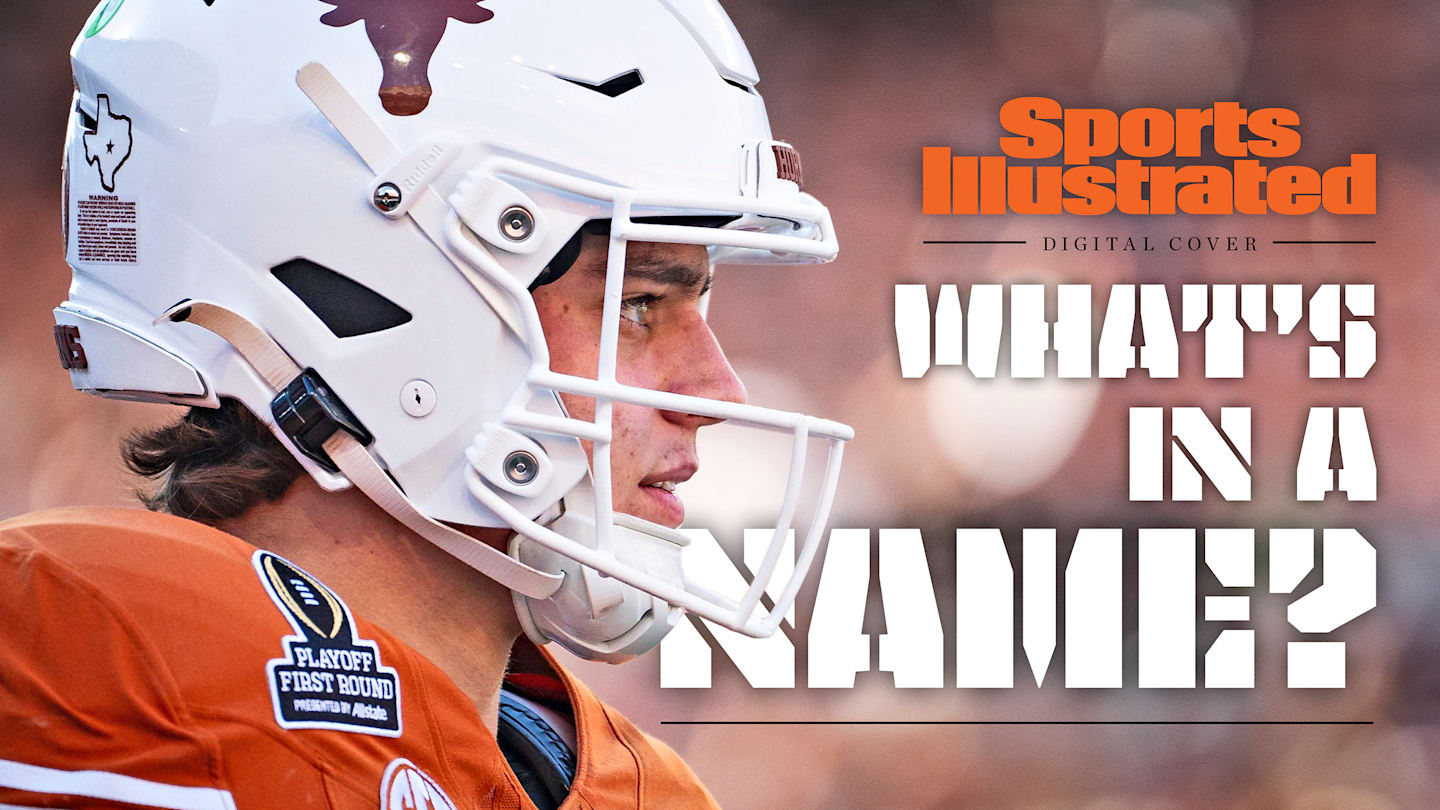

Arch Manning and the Enormous Expectations of His Family Fame

Arch Manning was around 6 years old when he identified the central conflict in his life today: “I really want to be a good football player,” he told his family on a car ride, “but I don’t want to be famous.” His younger brother, Heid, offered a solution: “Just keep your helmet on all the time.”It has not worked.Arch owns the 2025 college football season in the way that people in his native New Orleans often end up holding food and drinks they have no recollection of ordering. Officially, Arch is replacing Quinn Ewers as Texas’s starting quarterback. But to the public, he is a cultural replacement for his grandfather, Archie, and his uncles, Peyton and Eli.Arch has started just two games for the Longhorns, but sportsbooks have installed him as the Heisman Trophy favorite. He has thrown just 95 college passes, but fans are buzzing that he might be the No. 1 pick in next year’s NFL draft. Viewed coldly, and perhaps cynically: He is a famous college football player, but he has yet to prove he is a good one.He seems to know this. Arch has spent his whole football life doggedly dodging his own hype. (He declined to grant an interview to Sports Illustrated, presumably on the grounds that it would be an interview with Sports Illustrated.) When Arch was in middle school and his private passing coach, David Morris, realized he was special, Morris did not tell Arch’s parents. When college coaches began to focus on the kid as he entered high school, the Mannings sent word: Whatever you do, do not offer this kid a scholarship yet. When dozens of offers eventually came, Arch had to be coaxed into taking official visits. When he was invited to the Elite 11 quarterback competition, he turned it down. This might seem like his parents were protecting him from the spotlight, but the truth is, he didn’t want to go to Elite 11.Arch Manning is both a sophomore in college and the star of a movie he has chosen not to watch. It’s just as well. The movie is only loosely based on a true story. For a long time, people got his birth year wrong. His mom, Ellen, says, “I’ve even tried to change it on Wikipedia and they won’t let me.” Nothing says “America in 2025” quite like the nation telling a woman she is wrong about the day she gave birth. (“I was there,” Ellen says. “He was 10-and-a-half pounds. I’m not gonna forget that.”) On April 27 of this year, his dad, Cooper, wished him a happy 21st birthday on Instagram, and only then did Wikipedia change his birth year from 2005 to 2004.Quarterback is the most scrutinized position in sports, and arguably the most complicated. At its essence, though, quarterback is about doing the right thing at the right time without worrying about the stakes. In that sense, especially, Arch is fortunate to be a Manning.Though he has started just two games for the Longhorns, Arch is poised to soar this season, which would come as no surprise to his dad, and first backer, Cooper (with Arch in 2008). | Bill Frakes/Sports IllustratedThis is so obvious that it shouldn’t need to be said, but it does: The parents who raised Arch had a greater influence on him than the uncles who lived far away. Cooper jokes that, judging by public perception, he and Ellen “must have been in Sri Lanka while Peyton and Eli raised him.” The reality, Cooper says, is that Eli has never seen Arch play a game in person for the simple reason that he lives 1,300 miles away and has four children of his own.Cooper, who is Peyton and Eli’s older brother, was set to play wide receiver at Ole Miss until a spinal stenosis diagnosis ended his career. That condition is genetic but not inherited, so Cooper’s children were free to try anything. When Arch was a kid, his parents had him play soccer, baseball, golf, tennis and basketball. They put him in a pool, they had him try pottery, they sent him to wilderness camp, they wanted him to play an instrument. They learned that his preferred instrument was a football, his favorite swimming stroke was football, and he thought the wilderness would be a good place to play football.Arch did not join the family business; he chose a business other family members also chose. It’s an important distinction.“We just were raising our kids,” Ellen says. “When he was the No. 1 recruit, we were kind of like, ‘Really? This is weird.’ ”Arch with his grandfather, Archie, in 2008. | Bill Frakes/Sports IllustratedCooper and Ellen wanted Arch (and Heid, and their daughter, May) to understand that privilege went much deeper than having a famous name. Arch has never woken up on Christmas morning in the same city as Peyton or Eli, but he did share a house for extended periods with high school teammates who needed a place to stay. Some players view name, image and likeness deals as a way to pay their parents’ rent. Cooper says he and Arch have never even discussed NIL. Ellen points out that even when the Mannings told recruiters to hold off, “We had the luxury: We could sit back and let people be interested.”They were, of course, extremely interested. But while recruiting services hyped and fans salivated, Arch was affected, most of all, by the Manning they mostly forgot.“We, in this house in particular, live under the umbrella of Coop being the big star football player and having it all taken away from him,” Ellen says. “So everybody knows, ‘Hey, this could be over tomorrow.’ ”In another home, that could have bred impatience. In the Mannings’, it had the opposite effect: Whatever seems like a big deal now might not even matter in a week, so don’t get caught up in it. Many players at the top of the recruiting rankings expect to start as freshmen, but Arch thought he would benefit from sitting for at least a year.He took official visits to Georgia, Alabama and Texas, a trio that makes more sense now than it did then. Georgia was the defending national champion. Alabama was the premier program in the country. Texas had just gone 5–7 in Steve Sarkisian’s first year in Austin. But every great quarterback must excel at anticipation, and Arch looked at more than just the most recent standings.Arch Manning took official college visits to Georgia, Alabama and Texas before settling on the Longhorns and coach Steve Sarkisian. | David E. Klutho/Sports IllustratedGeorgia’s offensive coordinator at the time was Todd Monken. Alabama’s was Bill O’Brien. Arch knew that great offensive coordinators tend not to stick around very long. But he had watched Sarkisian’s offenses at Alabama, and since Sarkisian was both play-caller and head coach at Texas, there was really no other job for him to take. To most fans, Georgia and Alabama were the sure things and Texas was the unknown. But for a quarterback who valued system stability, Texas was the sure thing and Georgia and Alabama were unknowns.“From a quarterback standpoint, I think that’s a massive advantage,” Cooper says. “There is no threat of losing the coordinator.”Monken is now with the Ravens as offensive coordinator, O’Brien is head coach at Boston College and seven of the top eight quarterbacks in Arch’s recruiting class have transferred. But Sarkisian is still at Texas, designing plays for Arch Manning.The irony of fans assuming Arch will be great is that the Mannings are hyperaware of every factor outside a quarterback’s control. Archie spent a decade running for his life with the Saints, which led to Eli forcing a draft-day trade from a Chargers organization with a reputation for dysfunction to a Giants franchise noted for its stability. Peyton would have thrived anywhere, but Indianapolis was perfect for him: When he arrived, it was not quite a football town, and so there was no resistance to him turning the franchise into his fiefdom, to everyone’s benefit. Eli thrived in New York, in part, because he is incapable of being lured into a circus.Arch knows himself well enough to understand that, while he doesn’t seek fame, he needs to manage it. Only 114,000 people live in Tuscaloosa, and when you are Alabama’s starting quarterback, they all want to help you brush your teeth. Athens is only slightly larger, though it is less suffocating. Austin is a city of a million people, quite a few of whom would rather “Keep Austin Weird” than watch the local college kids play football. Arch recognized that Texas was a program with national championship potential in a city that prides itself on having other things to do.“Arch would prefer never to be in the paper or take a picture or do a commercial, or do anything that would require attention on him,” Cooper says. “He has no interest in it.”Arch, according to his family, would rather stay out of the spotlight, but does pitch in during Manning Passing Academy duties, including a Raising Cane’s shift this summer. | Kaitlyn Morris/Getty Images for Raising Cane’sEllen notes that Arch “deletes his Instagram all the time—he gets annoyed and gets rid of it.” But companies do not pay athletes for private endorsements, and so Arch publicizes his deals with, among others, Red Bull and Vuori. This is good for his bank balance and probably good for his head as well. Trying to avoid attention entirely would be exhausting.So far, Arch has done a masterful job of recognizing the undue hype without succumbing to it. When reporters asked him about Ewers this spring, Arch said, “It’s probably pretty annoying having me as the backup, just with all the media stuff. But he handled it like a champ.” Ellen says, “We have a family rule that you can’t ever read the comments.”Cooper says he and Arch have never discussed the Heisman. It’s unlikely that Archie, Peyton or Eli will bring it up. After all, none of them won it.The most famous family dynasty in football history has endured a surprising amount of failure. Archie Manning spent his NFL career trying to lug overmatched Saints teams into field goal range; his record as a starter was 35-101-3. Peyton’s Tennessee teams went 0–4 against Florida, and he did not win an NFL playoff game until his sixth season. In Eli’s first four NFL seasons, he threw almost as many interceptions (64) as touchdown passes (77).This is, of course, not how we think of the Mannings—nor should it be. But there were moments when it was how they thought of themselves.Cooper and Ellen remember going to Indy for a game when Peyton was a rookie. They were staying at his place, which seemed like a reasonable idea until they were stuck under the same roof as Peyton Manning after his team lost. Hurricane Georges was heading for New Orleans, leaving Cooper and Ellen with a choice between two storms. They flew to Atlanta to get away from both.Even true greatness can disappoint more often than it rewards. Fifteen of Peyton’s 17 NFL seasons ended in disappointment. Eli won two Super Bowls, but the Giants lost half the games he started, and he did not win a playoff game after he turned 31.For Arch, the ultimate benefits of being a Manning might come from watching the Mannings before him. Plenty of kids in Arch’s generation consume sports in short bursts on YouTube or social media, but every weekend, Arch watched at least two full NFL games because he wanted to watch his uncles. “He would sit there with his sweatbands on,” Cooper says. During commercial breaks, Arch would fire passes to his mom or dad in the entryway of their home. Watching Peyton and Eli play full games and full seasons prepared Arch for the ebbs and flows of playing quarterback, in a way that highlights of a stranger never could.Arch, here scoring in the Longhorns’ 52–0 stampede over Colorado State last season, is set to lead a Texas offense built around his skills. | Tim Warner/Getty ImagesSays Cooper: “This is a sport. It’s fun. Enjoy it. Practice, do everything you can to get better and perfect your craft, because you love doing it. If you add anything more than what it is, you’re kind of … I don’t know, wasting your time.” He is right, of course. But while he whispers into one of Arch’s ears, the rest of the country is screaming in the other.Olivia Manning, Arch’s grandmother, has already warned Ellen: “Something’s gonna happen, and they’re gonna turn on him.” He can delay the blowback by playing great, but that will make it worse when it arrives. Cooper remembers the pressure on Peyton to win a Super Bowl, “getting yelled at for not being able to win the AFC championship at times, when other people in the division had already been home for a couple weeks and no one’s on them.”Around the country this fall, football fans will watch Arch to see if he has Peyton’s head, Eli’s cool or Archie’s toughness. Or some combination of all three. “What he got,” his mother says, “was the obsession.” This season belongs to Arch Manning, but all he ever wanted was the ball.More College Football on Sports IllustratedListen to SI’s new college sports podcast, Others Receiving Votes, below or on Apple and Spotify. Watch the show on SI’s YouTube channel.